Nicaraguan-born American artist, Dino Aranda came to study at the Corcoran School of Arts and Design in Washington D.C. in the fall of 1965when he was twenty years old. He remembers that it was in October, because the leaves were changing and the winter chill was approaching. He did not have enough warm clothes but he had a dream. A few months later a fellow student gave him the phone number of Werth (“Mark”) V. Zuver as a contact person who was trying to start an art gallery. Aranda introduced Peruvian sculptor Manuel Pereira toZuver and this is how the collaboration between Aranda, Pereira and Zuver began that ultimately led to the formation of Fondo del Sol as a non-profit in 1973.

Similarly, as Praxis Galeriain Managua, Fondoprovided a space for collaboration and exhibition. It originally provided a workshop for a group of artists and writers from the Americas, and eventually grew into the second largest Spanish-speaking and Hispanic oriented museum in the United States during this time, sponsoring over 150 exhibitions of primarily Hispanic and other minority artists.

One of the first major projects at Fondowas compiling a research directory of Latin American artists living in the United States and then in 1977, organizing an exhibit of their work. The result was “Ancient Roots/New Visions.” The show traveled to nine cities in the United States and to Mexico City. It was a milestone in that it was the first important exhibition of Chicano, Puerto Rican and other Latin American artists living in the United States. Aranda exhibited his work, “Tres Figuras” in Ancient Roots/New Visions, which is now in the permanent collection at National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., and a work titled “Managua,” a mixed media on board.

Other notable exhibitions at Fondo included Aranda’s collaboration with the Chilean-born artist, Juan Downey in a two-man exhibition titled “Figures and Context” in 1979. Fondo del Sol was also one of the first museums to exhibit the works of Cuban-born artist, Ana Mendieta.

Fondo del Sol was also there for the greater Washington, D.C. community. During the 1980s and early 1990s Fondo was very active in sponsoring and participating in cultural events in the D.C. area. Additionally, Fondoparticipated in National Hispanic Heritage Week, declared by President Jimmy Carter. They sponsored an art festival, with food and music that drew more than 10,000 people.

Public funding for Fondo del Sol came from the National Endowment for the Arts, the D.C. Commission for the Arts and Humanities, and the D.C. Neighborhood Planning Councils, as well as private funding from such sources as the AT&T and Ford Foundations. This funding was the result of hard work in writing proposals for grants, which was another activity Aranda participated in as co-founder of Fondo.

In addition to his work with Fondo del Sol, Aranda was actively involved in expanding the reach of his creative process by becoming involved in media production. He was introduced to the possibilities of artistic expression offered by video as a medium through the two-man show he did with Juan Downey, based on Downey’s work with the Yanomami Indians in Brazil. The collaboration influenced Aranda to expand his work into video form. In 1980 he co-founded Tresamericas Productions, co-producing and directing a number of bilingual videos on the Latin American experience with Mary Lou Reker. The most extensive of these was “Liberation Theology: Its Impact,” funded by Intermedia-National Council of Churches, the D.C. Community Humanities Council and the New York Council for the Humanities, shown on PBS in 1983. It is currently in the permanent collection of numerous video libraries, including the Ringling Museum in Florida, which contains a number of items in Aranda’s artist file.

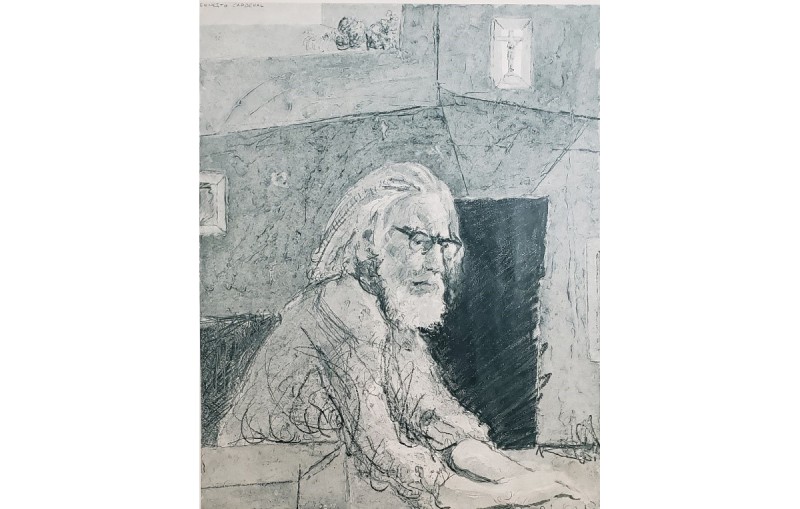

Aranda’s interest in liberation theology was sparked by his work with Ernesto Cardenal, who, in addition to being a poet, was a priest and an icon of liberation theology. The goals of liberation theology are two-fold, the first is to provide a theology that leads to liberation from oppression. Oppression comes in many forms, including social, economic, racial, sexual, religious or political. Liberation theology, therefore, has many faces, depending on the form of oppression being addressed.

In the context of Latin America, oppression during the ‘70s and ‘80s was multifaceted. These where countries were 5% of the population controlled 80% of the resources of a country’s wealth. These countries, along with those in Africa and Asia formed the “Third World,” in which the “First World” or developed nations controlled the economic systems that locked the Third World out. During the 1970s developmental theory began to provide a model for understanding the structure for explaining the causes of this oppression.

In the context of Nicaragua, the corrupt regime of Anastasio Somoza aligned itself with the traditional Roman Catholic Church. Liberation theology was an expression against the oppression of the poor by this political-religious alliance.

This leads us to the second goal of liberation theology, which is to foster grassroots Christian communities, small groups of oppressed people gathering to reflect on their experiences, their faith and their reading of the Bible to lead them to liberation from oppression. In this sense, liberation theology partially borrowed from Marxism in its analysis of the class struggle and the harsh capitalism that oppressed the poor but, it never adopted Communism in its pure form, as some have accused it of being.

During the civil wars that engulfed not only Nicaragua but also the other countries of Central America, the voices of liberation theologians advocating for poor and indigenous communities grew louder, causing a schism between the traditional Catholic Church and liberation theologians. One of the loudest voices during this era was that of Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador, who was assassinated at the alter for his advocacy of the oppressed. In Nicaragua, Ernesto Cardenal also suffered because of his belief in liberation theology. Pope John Paul II took away Cardenal’s priestly functions.

But now the tide has turned. In Pope Francis, there is now a liberation theologian who is the pope. Pope Francis has declared Archbishop Romero a saint in 2018, and shortly before Cardenal’s death in 2020, Pope Francis absolved him from all his canonical censorships. We live in different times.

However, in the 1970s and 1980s, work such as Dino Aranda’s and Mary Lou Reker’svideo production Liberation Theology: It’s Impact was an important introduction of liberation theology for the American audience, leading to greater acceptance of this important doctrine that slowly paved the path for Pope Francis’ move to the Vatican.